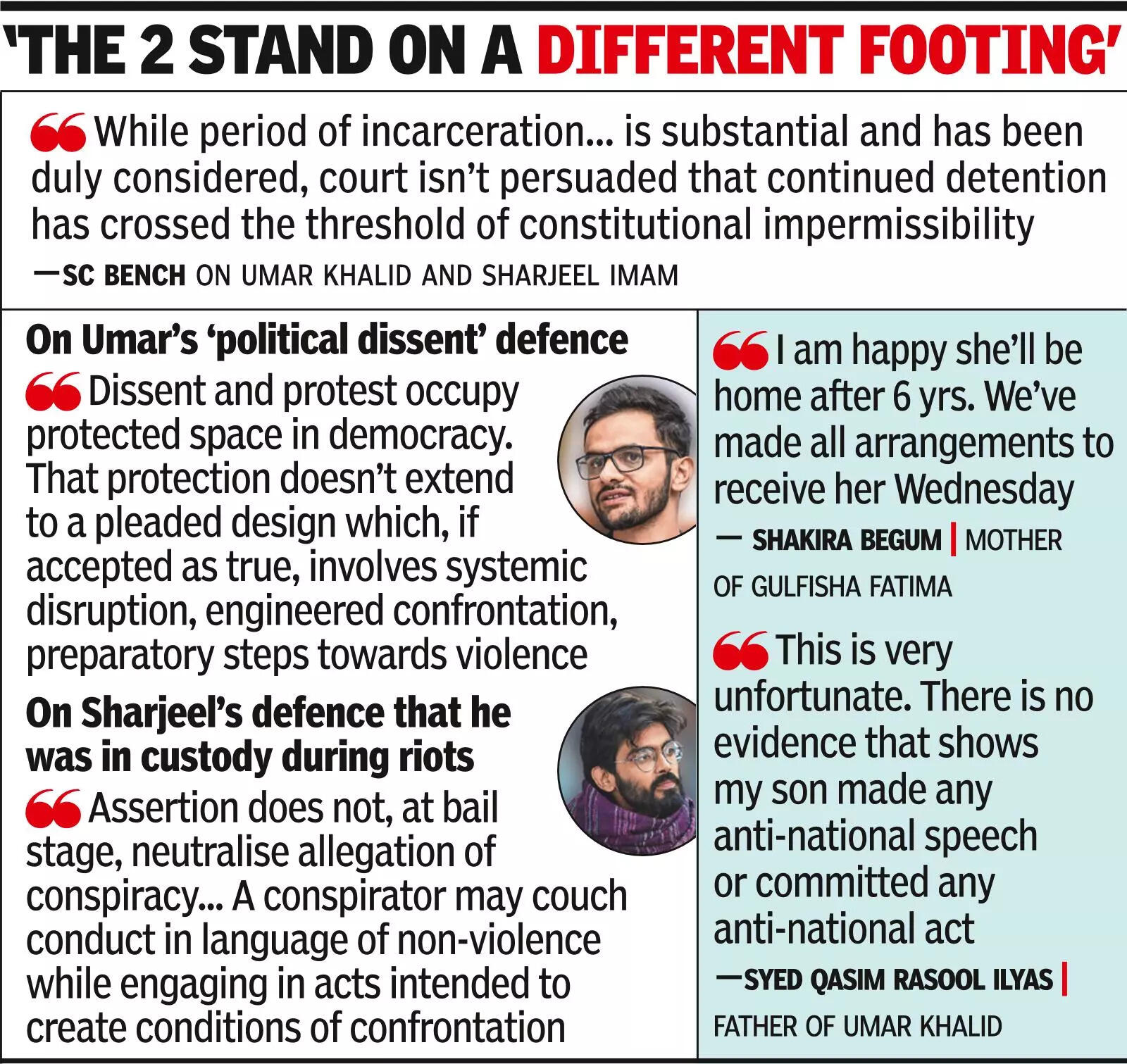

NEW DELHI: Holding that delay in trial and long incarceration cannot be a “trump card” to get bail in UAPA offences and that a court cannot treat liberty of an accused as the sole criterion and societal security as peripheral, Supreme Court Monday rejected bail pleas of student activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in the Delhi riots case but granted relief to other five co-accused — Gulfisha Fatima, Meeran Haider, Shifa-ur-Rehman, Mohd Saleem Khan and Shadab Ahmad.

The case relates to protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act turning violent, leading to communal clashes during the visit of US President Trump in 2020.Khalid and Imam, who along with others have been in jail for over five years, may have to spend another year in prison as the bench of Justices Aravind Kumar and N V Anjaria said they can apply afresh after a year or after all protected witnesses have been examined, whichever is earlier.The bench cited “hierarchy of culpability” to say Khalid and Imam stood on a different footing than the others.

What explains inconsistencies in deciding bail pleas in recent past

Granting bail is the discretionary power of a court and the outcome of a bail plea largely depends on the approach of a bench and that perhaps explains inconsistency of Supreme Court’s in the recent past in deciding cases, particularly those related to serious offences under special acts like PMLA and UAPA which provide stringent bail conditions..In some cases, like those of former Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal and Tamil Nadu minister, Senthil Balaji, accused’s constitutional right to speedy trial was given precedence over the seriousness of the alleged offence and bail was granted on the ground of long incarceration and delay in trial. In some others; for instance, Gurvinder Singh v State of Punjab, gravity of the offence has been the deciding factor, with SC expressly cautioning against the mechanical invocation of prolonged incarceration as a ground for bail in cases involving serious offences under special enactments.While dealing in UAPA case, a three judge bench had in 2021 held that Section 43D(5) of UAPA per se does not prevent constitutional courts to grant bail on grounds of violation of fundamental rights of accused. “Courts are expected to appreciate legislative policy against grant of bail but the rigours of such provisions will melt down where there is no likelihood of trial being completed within a reasonable time and the period of incarceration already undergone has exceeded a substantial part of the prescribed sentence,” Justice Surya Kant, now the CJI, who penned the judgement for the bench said. Justice Kant had said such an approach would safeguard against the possibility of provisions like Section 43D (5) of UAPA being used as the sole metric for denial of bail or for wholesale breach of constitutional right to speedy trial.While rejecting bail plea of Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, a bench of Justices Aravind Kumar and N V Anjaria referred to 2021 judgement and said “The same decision, however, does not indicate as laying down a mechanical rule under which the mere passage of time becomes determinative in every case arising under a special statute. The jurisprudence of this Court does not support a construction whereby delay simpliciter eclipses a statutory regime enacted by Parliament to address offences of a special category.“It said the proper constitutional question, therefore, is not whether Article 21 (right to life and liberty) is superior to Section 43D (5) of UAPA dealing with the higher bail threshold. “The proper question is how Article 21 is to be applied where Parliament has expressly conditioned the grant of bail in relation to offences alleged to implicate national security. The law does not contemplate an either-or approach. Nor does it contemplate an unstructured blending of statutory and constitutional considerations. What is required is disciplined judicial scrutiny that gives due regard to both”.While granting bail to an accused in 2024 who was under custody for four years and trial had not initiated, SC had said the “the over-arching postulate of criminal jurisprudence that an accused is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty cannot be brushed aside lightly, howsoever stringent the penal law may be”.The court had said, “If the State or any prosecuting agency including the court concerned has no wherewithal to provide or protect the fundamental right of an accused to have a speedy trial as enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution then the State or any other prosecuting agency should not oppose the plea for bail on the ground that the crime committed is serious. Article 21 of the Constitution applies irrespective of the nature of the crime.”In an important ruling, SC in 2024 held that the conventional idea ‘bail is the rule, jail is an exception’ should be applicable not only to IPC offences but also other offences for which special statutes have been enacted like UAPA if the conditions prescribed under that law are fulfilled.In cases of Khalid and Imam the court emphasised that they also contributed to the delay in trial.